Tuesday, March 18, 2008

The Week That Shook Wall Street -- The Wall Street Journal Online Edition

## This Wall Street Journal Artical needs to be preserved

## as part of wall street history and a MBA case.

##

DOW JONES REPRINTS

This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, use the Order Reprints tool at the bottom of any article or visit:

http://www.djreprints.com/.

• See a sample reprint in PDF format.

• Order a reprint of this article now.

The Week That Shook Wall Street:

Inside the Demise of Bear Stearns

By ROBIN SIDEL, GREG IP, MICHAEL M. PHILLIPS and KATE KELLY

March 18, 2008; Page A1

The past six days have shaken American capitalism.

Between Tuesday, when financial markets began turning against Bear Stearns Cos., and Sunday night, when the bank disappeared into the arms of J.P. Morgan Chase & Co., Washington policy makers, federal regulators and Wall Street bankers struggled to keep the trouble from tanking financial markets and exacerbating the country's deep economic uncertainty.

The mood changed daily, as did the apparent scope of the problem. On Friday, Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson thought markets would be calmed by the announcement that the Federal Reserve had agreed to help bail out Bear Stearns. President Bush gave a reassuring speech that day about the fundamental soundness of the U.S. economy. By Saturday, however, Mr. Paulson had become convinced that a definitive agreement to sell Bear Stearns had to be inked before markets opened yesterday.

Bear Stearns's board of directors was whipsawed by the rapidly unfolding events, in particular by the pressure from Washington to clinch a deal, says one person familiar with their deliberations.

"We thought they gave us 28 days," this person says, in reference to the terms of the Fed's bailout financing. "Then they gave us 24 hours."

In the end, Washington more or less threw its rule book out the window. The Fed, which has been at the forefront of the government response, made a number of unprecedented moves. Among other things, it agreed to temporarily remove from circulation a big chunk of difficult-to-trade securities and to offer direct loans to Wall Street investment banks for the first time.

The terms of the Bear Stearns sale contained some highly unusual features. For one, J.P. Morgan retains the option to purchase Bear's valuable headquarters building in midtown Manhattan, even if Bear's board recommends a rival offer. Also, the Fed has taken responsibility for $30 billion in hard-to-trade securities on Bear Stearns's books, with potential for both profit and loss. The question now looming over the transaction: Has the government set a precedent for propping up failing financial institutions at a time when its more traditional tools don't appear to be working? Cutting interest rates -- which the Fed is expected to do again today, by between a half percentage point and a full point -- hasn't yet done much to loosen capital markets gummed up by piles of bad debt.

Even though the transaction ultimately could leave taxpayers on the hook for losses, the political response so far has been fairly positive. "When you're looking into the abyss, you don't quibble over details," said New York Democratic Senator Charles Schumer.

Tuesday, March 11

From the earliest days of the financial crisis that began last year, the Federal Reserve had been working on contingency plans to lend to investment banks. Such firms regularly asked for government help to finance their large inventories of securities such as mortgage-backed bonds. They hoped to get the same favorable terms the Fed also gave to banks that borrow from its "discount window." But the Fed is barred from making such loans to firms that aren't banks, except by invoking a special clause which it hadn't used to lend money since the Great Depression. Officials worried that the drama surrounding a decision to do something for the first time since the 1930s could be damaging to confidence.

On Tuesday, officials unveiled what they thought came close: a promise to lend up to $200 billion in Treasury bonds to investment banks for 28 days. In return, the Treasury would get securities backed by home mortgages, whose uncertain values helped spark the current crisis, and other hard-to-trade collateral. The first swap was scheduled for March 27. At first, the firms were elated.

That same day, the market began turning on Bear Stearns. Phones were ringing off the hook at rival firms such as Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Morgan Stanley and Credit Suisse Group. Clients of those firms were growing worried about trades they had entered into with Bear Stearns -- about whether Bear Stearns would be able to make good on its obligations. The clients asked the other investment banks whether they would be willing to take the clients' places in the trades. But credit officers at Goldman, Morgan Stanley and others -- worried themselves about Bear Stearns's condition -- began to say no.

At Bear Stearns, Chief Financial Officer Samuel Molinaro, along with company lawyers and Treasurer Robert Upton, were trying to make sense of the situation. They felt comfortable with their capital base of roughly $17 billion and were looking forward to reporting Bear Stearns's first-quarter earnings, which had been respectable amid the market carnage.

One theory began developing internally: Hedge funds with short positions on Bear -- bets that the company's stock would fall -- were trying to speed the decline by spreading negative rumors.

For the first part of the week, Chief Executive Officer Alan Schwartz was out of pocket. Although Bear Stearns had been struggling with mortgage-related losses and problems in its wealth-management unit, Mr. Schwartz was hosting a Bear Stearns media conference in Palm Beach, Fla. On Wednesday morning, he left the conference briefly to do an interview with CNBC in an effort to deflect rumors about liquidity issues at the firm.

Thursday

On Thursday evening, after customers had continued to pull their money out of Bear Stearns, the bank reached out to J. P. Morgan, looking to discuss ways the Wall Street giant could help ease Bear's cash crunch.

By then, Bear Stearns's cash position had dwindled to just $2 billion. In a conference call at 7:30 p.m., officials at Bear Stearns and the Securities and Exchange Commission told Fed and Treasury officials that the firm saw little option other than to file for bankruptcy protection the next morning.

Bear Stearns's hope was that the Fed would make a loan from its discount window to provide several weeks of breathing room. That, the firm hoped, would perhaps halt a run on the bank by allowing it to swap bonds for the cash necessary to return to customers.

The Fed's standard preference in dealing with a troubled institution is to first seek a private-sector solution, such as a sale or financing agreement. But the possibility of a bankruptcy filing Friday morning created a hard deadline.

A trigger point was looming for Bear Stearns in the so-called repo market, where banks and securities firms extend and receive short-term loans, typically made overnight and backed by securities. At 7:30 a.m., Bear Stearns would have to begin paying back some of its billions of dollars in repo borrowings. If the firm didn't repay the money on time, its creditors could start selling the collateral Bear had pledged to them. The implications went well beyond Bear Stearns: If other investors questioned the safety of loans they made in the repo market, they could start to withhold funds from other investment banks and companies.

The $4.5 trillion repo market isn't a newfangled innovation like subprime-backed collateralized debt obligations. It is a decades-old, plain-vanilla market critical to the smooth functioning of capital markets. A default by a major counterparty would have been unprecedented, and could have had unpredictable consequences for the entire market.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York President Timothy Geithner worked into the night, grabbing just two hours of sleep near the bank's downtown Manhattan headquarters. His staff spent the night going over Bear's books and talking to potential suitors including J. P. Morgan. The hard reality was that even interested buyers said they needed more time to go over the company.

The pace and complexity of events left Bear's board of directors groping for answers. "It was a traumatic experience," says one person who participated. Sleep deprivation set in, with some of the hundreds of attorneys and bankers sleeping only a few hours during a 72-hour sprint. Dress was casual, with neckties quickly shorn.

Friday

At 5 a.m. Friday, Mr. Geithner, Mr. Paulson and Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, calling in from home, joined a conference call to debate whether Bear should be allowed to fail or whether the Fed should lend it enough money to get through the weekend. At 7 a.m. they settled on the lifeline option. Mr. Bernanke assembled the Fed's other three available governors to vote for the loan, the first time since the Depression the Fed would use its extraordinary authority to lend to nonbanks.

The Fed announced that it would lend Bear money, through J.P. Morgan, for up to 28 days to get the venerable investment bank through its cash crunch. At 9 a.m., Mr. Geithner, Mr. Paulson and aides addressed a conference call of bond dealers and bankers. Mr. Paulson took the lead, saying the dealer community had "a stake" in the overall deal working out.

But the markets didn't take well to the news that a major investment bank was on the brink of failure. Stocks sank. Other investment banks were seeing lenders turn cautious. Fed officials led by Bill Dudley, head of open-market operations, began planning a more direct response: opening the discount window to all investment banks, a request the Fed had resisted for months.

J.P. Morgan's effort to buy Bear kicked into high gear on Friday afternoon, just hours after the big bank and the Fed had provided Bear with the 28-day lifeline. Steve Black, co-head of J.P. Morgan's investment bank, returned early from vacation in the Caribbean, spearheading the bank's efforts with his J.P. Morgan counterpart in London, Bill Winters.

Mr. Black's role was pivotal. He was a longtime associate of J.P. Morgan Chief Executive James Dimon. And Mr. Black had a long relationship with Bear's CEO, Mr. Schwartz, dating back to the 1970s, when the two were fraternity brothers at Duke University.

J.P. Morgan bankers were broken into some 16 teams -- all with specific due-diligence assignments. Some focused on Bear's prime-brokerage business, which was attractive to J.P. Morgan. Others concentrated on technical operations, commodities, and the like.

As some Fed staffers worked from a conference room on Bear's 12th floor, Federal Reserve officials insisted that the firm complete a deal that weekend. Officials made it clear the loan was only for the short term to ensure a deal got done as quickly as possible. Their priority was that Bear's counterparties -- the parties that stood on the other side of its trades -- would be able to arrive at work Monday knowing their contracts were good, minimizing the risk of a generalized flight from the markets.

Treasury Secretary Paulson knew that the day's work wouldn't be enough to keep Bear afloat over the long term. Still, Mr. Paulson, a former Goldman Sachs chief executive and the administration's point man for financial markets, thought Bear Stearns would survive through the weekend.

Saturday

That illusion was shattered Saturday morning, when Mr. Paulson was deluged by calls to his home from bank chief executives. They told him they worried the run on Bear would spread to other financial institutions. After several such calls, Mr. Paulson realized the Fed and Treasury had to get the J.P. Morgan deal done before the markets in Asia opened on late Sunday, New York time.

"It was just clear that this franchise was going to unravel if the deal wasn't done by the end of the weekend," Mr. Paulson said in an interview yesterday.

A year ago, Mr. Paulson wouldn't have considered Bear Stearns big enough that its collapse would present a threat to the U.S. financial system. But confidence in the economy and financial sector are so shaky now that he had no doubt that the Fed and government had to act to prevent its bankruptcy, according to a senior Treasury official.

At 8 a.m. Saturday, the J.P. Morgan bankers assembled to receive instructions in the bank's executive offices, located on the 8th floor of its Park Avenue headquarters. One hour later, they headed down the street to Bear Stearns's headquarters to pore over Bear's books. Due diligence had begun.

Back at J.P. Morgan's headquarters, top executives set up war rooms on the executive floor, commandeering offices of colleagues who weren't directly involved in the negotiations. Bankers darted in and out of offices searching for the top brass, who were also moving from room to room. Mr. Dimon, wearing slacks and a dark sweater, urged the bankers to stay calm and focused. "Everyone take a deep breath," he said at one point.

By 7:30 p.m., hunger pangs had taken hold. Someone ordered Chinese food. A security guard lay out a buffet spread.

That evening, Mr. Black got on the phone to Mr. Schwartz, Bear Stearns's CEO. J.P. Morgan would be willing to buy Bear Stearns, subject to the conclusion of due diligence, he told Mr. Schwartz. The J.P. Morgan executives didn't set a specific price, instead providing a dollars-per-share range, according to people familiar with the matter. At the high end was a figure in the low double digits, these people say.

By 1 a.m., the bankers headed home for a few hours of sleep.

Sunday

Early the next morning, Messrs. Dimon and Black and other top executives sat around a conference-room table to discuss the situation. One by one, they began expressing concern about the speed at which the situation was progressing. They weren't comfortable with the level of due diligence being conducted. Were there more problems hidden deep in Bear's balance sheet that they hadn't found yet? Would market turmoil result in more problems? Was J.P. Morgan really willing to take such a risk without full information?

"Things didn't firm up -- they got more shaky," according to one person familiar with the meeting.

Finally, they came to a conclusion. J.P. Morgan wouldn't buy Bear Stearns on its own. The bank needed help before it would do the deal.

Mr. Paulson was frequently on the phone with Bear and J. P. Morgan executives, negotiating the details of the deal, the senior Treasury official said. Initially, Morgan wanted to pick off select parts of Bear, but Mr. Paulson insisted that it take the entire Bear portfolio, the official said.

This was no normal negotiation, says one person involved in the matter. Instead of two parties, there were three, this person explains, the third being the government. It is unclear what explicit requests were made by the Fed or Treasury. But the deal now in place has a number of features that are highly unusual, according to people who worked on the transaction.

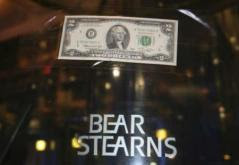

In addition to its option to purchase Bear's headquarters building, J.P. Morgan has the option to purchase just under 20% of Bear Stearns's shares at a price of $2 each. That feature gives J.P. Morgan an ability to largely block a rival offer, says a person with knowledge of the contract.

The deal also is highly "locked up," meaning that J.P. Morgan cannot walk, even if there is a heavy deterioration in Bear's business or future prospects. Bear Stearns holders can, of course, vote the deal down. But the effect that would have on J.P. Morgan's ongoing managerial oversight and the Fed's guarantees is largely unknown.

"We're in hyperspace," says one person who worked on the deal. All these matters are very likely to be litigated in court eventually, this person adds.

The Fed spent the weekend putting together a plan to be announced Sunday evening, regardless of the outcome of Bear's negotiations, that would enable all Wall Street banks to borrow from the central bank. Mr. Bernanke called the Fed's five governors together for a vote Sunday afternoon. All five voted in favor, using for the second time since Friday the Fed's authority to lend to nonbanks.

The steps were announced at the same time the Fed agreed to lend $30 billion to J.P. Morgan to complete its acquisition of Bear Stearns. The loans will be secured solely by difficult-to-value assets inherited from Bear Stearns. If the assets decline in value, the Fed -- and therefore the U.S. taxpayer -- will bear the cost.

Aware of the potential political backlash, Fed and Treasury officials briefed Democrats throughout the weekend. Events moved so fast that there was little time for much substantive outreach. Mr. Bernanke spoke with Massachusetts Democrat and House Financial Services Committee Chairman Barney Frank on Friday. Fed staffers emailed updates to Mr. Frank's office on Sunday.

"I believe this is the right action that was taken over the weekend," said Senate Banking Committee Chairman Christopher Dodd of Connecticut, a Democrat, who spoke with Messrs. Bernanke and Paulson on Sunday during deliberations. "To allow this to go into bankruptcy, I think, would have [created] some systemic problems that would have been massive."

--Dennis K. Berman, Damian Paletta and Sarah Lueck contributed to this article.

Monday, March 17, 2008

Wall Street does not believe in tears

On Sunday evening, JPMorgan announced that it will acquire Bear Stearns for $240 million dollars or at $2 per share. The last trade of Bear Stearns’ stock on Friday on the New York Stock exchange was at $30.85 dollars. With full consideration for its potential costs and risks, JPMorgan has got a good deal. Its stock rose $3.01, or 8.2 percent, to $39.55 at 12:05 p.m. in New York Stock Exchange while the Amex Securities Broker/Dealer Index fell 14 percent today.

I got this news through an internal email at 7:55PM on Sunday. For me as well as the 14,000 fellow Bear Stearns employees, this news was a relief. We now knew that on Monday we would still have a place to go for work. The biggest losers of this fallout will be the equity holders. It is reported that Bear Stearns former CEO James Cayne and British investor Joseph Lewis each lost over $1 billion dollars. Besides institution investors, a big group of investors will be Bear Stearns employees who own up to 30 percent of the outstanding stocks. One of my colleagues said he had accumulated 4000 shares over his 17 years of careers with Bear Stearns. Now he is facing a double jeopardy of losing both his job and the bulk of his retirement savings. While I do not know what words to use on those ‘Wall Street sharks,’ I know that those rank and file employees do not deserve this punishment. Well, Wall Street does not believe in tears.

Nowadays, the world financial markets have developed into a tightly intertwined web. Once this web shows sign of fatigue, the government does not have much time to wait before intervening. Bear Stearns was a weak link. For Fed to let this one wound bring havoc to the entire financial market was not an option. If a $30 billion loan guarantee and a merge of JPMorgan and Bear Stearns created a small unfairness for a few, so let it be. Preventing a financial market meltdown from bringing down the whole economy was an overwhelming goal.

How did we get to this situation? Within Bear Stearns, many people blade former CEO James Cayne for his laid back management style. I agree. On the macroeconomic level however, I believe, we have to blame the formal Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan. After a meltdown of the internet bubble around year 2000, Greenspan kept interest rate low to stimulate the economy. While it was correct and effective to use monetary policy, Greenspan over did it. If Greenspan were a doctor, he kept his patient on blood transfusion too long. A patient who had developed dependency on external help would never stand up on himself. That patient was the economy under Greenspan. After becoming the new Fed Chairman in February 2006, Ben Bernanke attempted to use monetary policy to fight inflation. As soon as Bernanke raised interest rate, the housing market started to dive. The monetary policy had been abused in such that it could no longer be used for its textbook purpose.

Another reason for today’s meltdown lies in the technicality of today’s complex mortgage business model which has developed in such that originators, package makers, issuers and mortgage paper owners are separated. Given low cost of funding (remember Greeenspan?), the mortgage originators had all the incentives to lend. They did the lending as much and as fast as they could. Don’t you forget we are still a capitalist society? What if a loan would go bad and affect the mortgage owners, the originators could not care less. Stories have come out the mortgage lenders colluded with borrowers cheating on the paper work to get the loans approved. Because the mortgage business process was complicated, many of the mortgage owners knew less of what they should have known about those loan packages . Once they started to smell bad and started opening some of the boxes to look inside, bad news came out. As boxes after boxes of bad loans got exposed, we got to where we are.

P.S. The latest news on wire says that JPMorgan plans to cut half of the current Bear Stearns headcounts. Well, all I can do now is to hope that I can survive this cut. I would also like to offer my prayers to evey fellow Bear Stearns employees. For tonight, I wish we all sleep well. Tomorrow is another day.

Friday, March 14, 2008

The Party is over?

What a day! All of a sudden, people on the office floor changed. Everyone was nice to one another. Even those who had mostly maintained professionally stern faces started to greet people. We all knew that, for good or bad, our professional careers with this formerly Wall Street powerhouse will soon be over. Through out my career, I have never seen so many emails from top management delivered to my email inbox in a short span of a couple of hours. Multiple townhall meetings in a day? Never heard of. Today - Saturday, March 14, 2008 – will be remembered as a milestone. I know my job and my personal finance will inevitably be impacted but I am not bitter. I have not done anything to cause this and there was nothing I could have done to make a difference. I am amazed that what happens to a company with barely 14 thousand employees could have such a huge impact on the US economy. For today, I happend to be in the very center of a national financial storm. President Push happens to be in town today giving a speech at the New York economic club. I bet he was made aware of name of this Wall Street company.

Here is a 5-DAY re-cap of events surrounding Bear Stearns:

MONDAY

Bear Stearns DENIES Rumors on Liquidity After Shares Plummet (Bloomberg)

TUESDAY

Bear Stearns Falls For 2nd Day on Cash Concerns (Bloomberg)

WEDNESDAY

Bear Stearn's CEO Schwartz Says Cash Cushion is Ample (Bloomberg)

THURSDAY

Bear Stearn's Falls To 5-Year Low on Capital Concern (Bloomberg)

FRIDAY

Bear Stearns Gets EMERGENCY FUNDING From JPMorgan & Fed (Bloomberg)

Tuesday, March 4, 2008

Rules for engineering

I read with interest the article by our legal type doing the legal thing on legal leadership. (NB: Anyone besides me notice that there is a picture of him but no name... Whom is him?) The article resonated with me and helps me provide a structure for some of the basic tenants of leadership I follow as it relates to engineering management. So, here is a crack at some of the rules I live by. I will post more as time goes on:

Engineers should attend all key business and staff meetings.

Engineers are important players in key decisions because we understand the technology of “how” things work. The business team should decide why and what we do, but engineering has a significant understanding of the technology that can be useful in solving the business problems.

While attending these meetings, it is important to understand that influencing people and decisions is an important part of the job. Attacking or vilifying (technical arrogance anyone?) is bound to be counter-productive and lead to not only distractions but dissatisfaction and a subsequent waning of the influence that engineer might have had.

Eliminate the “No” word from your vocabulary.

Business teams make decisions and seek advice and input from engineering. It is really easy to explain why an idea is stupid. In fact, I can pay someone $5 an hour to tell me how bad an idea is. The point is that it is easy to shoot things down. It is much harder to figure out how to make things work, solve problems creatively and come up with a scenario that works both technically and for the business.

Additionally, it is important to quantify the decision criteria. Instead of saying “No, doing foo is a stupid idea”, engineers could say “At this time I don't know how to do foo” or “Doing foo will cost you n number of months of engineering time and n number of $. Balance that against existing tasks and tell me what you would like to do.” In this manner we accomplish our role (advise on what to do and how to do it) but still leave the decision maker the ability to make the decisions that count. This street credibility is invaluable. Helping our teams to make the correct decisions should be based on facts and influence, not technical nay saying.

Engineers should be business people. Hone your business ability.

The longer I am in engineering, the more convinced I am that doing is much simpler (for me) than figuring out what to do. I can build a computer (program, chip, application, utility etc.). The really hard thing (OK slightly tongue in cheek, engineering is hard too), at least for me, is figuring out what to build, when to build it and how to sell it. I am not detracting from the rare and beautiful talent associated with building and creating. These are great things and are the foundations of our success as an engineering centric company (and customer centric). Knowing that we need to build low cost, low power servers to take back market share in servers is genius however. (Did you hear we are number 3 again? Sorry Dell...)

Engineers must take every chance to be customer centric and customer focused. Jerry Vogel at AMD talks about customer centric engineering. I had the benefit of hearing Jerry speak when I attended the Experienced Managers Academy (essentially the “I wanna be a director” school for AMD leadership) and it was a profound experience. Jerry intuitively understands that success is defined by our partners and our partnerships with our customers. Business with our customers is and should be a personal thing. It is pretty clear to me that the AMD-Sun partnership is, well, a partnership.

Many of our (engineering's) customers are the marketing and sales teams. The entire value chain consists of building the right thing at the right time and sales/marketing will tell us this if we listen.

Finally, we are in business. Failing to understand key business statistics and metrics (ROI, WACC, ERP, TCO etc) prevents us from understanding how to influence either these statistics or the people that make decisions based on these statistics.

Return phone calls and email promptly.

Recall that one of the key roles for an engineer is to influence decision making. The frustration associated with not being able to reach an engineer or being able to solicit advice is extreme. It results in splits between team members and fracturing of relationships. Build and maintain those relationships such that when it really counts, the relationship and the problem solving and influencing skills are intact and ready for use.

Learn about business problems and proposed solutions early.

Some of my greatest success stories involve solving a problem with already crafted solutions before lots of money and effort were spent trying to spin up a new program. Since we are, in a sense, the technical historians of our business, we have a wealth of tested and produced solutions at our finger tips. If we are intimately involved in our business, we can put that history to use and use it to influence key decision makers.

Simplicity is beautiful.

A simple solution is far more elegant than a complex solution. I “made my bones” in writing software that tried to espouse the following guidelines:

The user should never need to ask the question “What do I do now?” The design should preclude the user from needing to reference a manual or look at something else to move forward. This is very hard to do and requires great sophistication.

Things should just work. No configuration, no hoops to jump through, no magic rocks to grok or arcane rituals to perform. Plug it in, turn it on and go. Anything else is a failure of the “what do I do now” rule. If you need to know the secret knock in order to proceed the design is flawed.

Write your code such that a new graduate can work in the code base without undue effort or initiation. There are no style points for complex code, terse commentary or mind bending and intricate interactions. Simple, discrete and straight forward code is beautiful. It reduces the total cost of ownership, eases maintenance and reduces sustaining costs. Most importantly it guarantees that I can bend my talents to solving new and interesting problems, not maintaining an obscure and difficult code base.

Monday, March 3, 2008

SHAME ON YOU, Honda Dealerships and Verizon Telephone companies

Being on call this week, I stayed up late last night working on a production issue. Early in the morning, a loud telephone ring waked me up. The caller ID showed the caller to be “UNKNOWN.” I guessed it might be from my mother in

“Hi, Mom,” I picked up the phone, still half asleep.

After 2 quick clicks, the other end started a recorded session, “this is a second warning. Your vehicle’s factory warranty will expire soon... It is very dangerous to drive a car without such a warranty… We will soon give you another warning…”

Throughout the whole day, I had a hard time to calm down. I was mad. SHAME ON YOU, North American Honda Dealerships. Like a bunch of rapists, you have just forced on me against my free will. My house phone was an unlisted and telemarketer blocked phone reserved for my own family usage. I paid special fees to setup those special phone services. While purchasing a car, I gave you this number to prove my ID for a bank loan. You have no right to break into my phone to deliver your marketing pitches. Your action has resulted in my unhappiness and ruined half day of my otherwise productive time.

SHAME ON YOU, the Verizon telephone company! You acted like a smooth con-artist. One day, you sold your customers a ‘service’ called ‘Caller ID.’ The next day, you turned around to sell the telemarketers another service to allow them to hide their phone numbers while making outgoing calls. You designed this clever scam which allowed you to collect money from both consumers and marketing business at same time. What you gave to them? Nothing, exactly that, nothing! Therefore, we have to call you what you are – a thief.